Deconstructing: Defending Denard Robinson, one tackle at a time

Breaking down how Alabama's defense plans to attack college football's most dynamic running quarterback -- and vice versa.

Saturday night's opener between Michigan and Alabama in Dallas is an automatic blockbuster, guaranteeing an intense, bowl-like atmosphere with two huge fan bases descending on a neutral site to do the "Big Ten vs. S! E! C!" thing writ large, with all that entails. Strategically, though, the matchup is every bit as fascinating: Between the best defense in the country, and arguably the most respected defensive mind, Alabama head coach Nick Saban, and arguably the most dynamic, scheme-busting quarterback, Michigan senior Denard Robinson, a pair of truly opposite numbers who present one another with unique challenges they're not accustomed to facing in their own leagues.

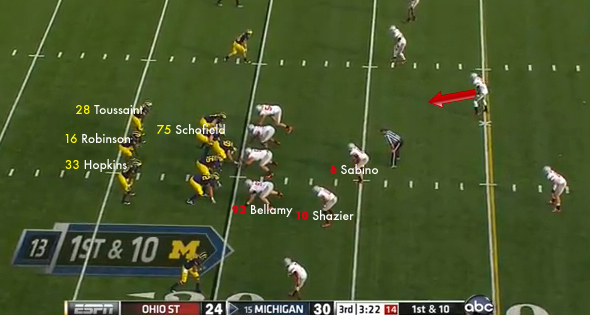

Punch. Against State" data-canon="Ohio Bobcats" data-type="SPORTS_OBJECT_TEAM" id="shortcode0"> last November, Robinson delivered one of the best performances in the history of the rivalry, hitting 14 of 17 passes for 167 yards and three touchdowns and adding two more scores to go with 170 yards rushing. The vast majority of that number came on a bread-and-butter counter play out of the shotgun that used All-Big Ten tailback Fitzgerald Toussaint (who racked up 120 on the ground himself) as a decoy to stretch the defense wide, and Robinson to attack the suddenly vulnerable middle behind a pulling guard.

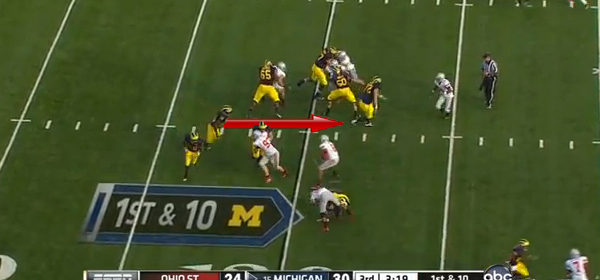

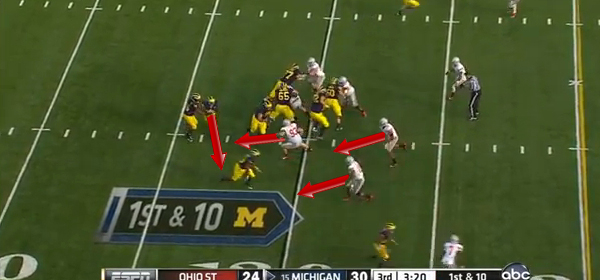

In this case, on a 1st-and-10 play in the third quarter, Michigan lined up with two backs on either side of Robinson, Toussaint and Stephen Hopkins, with three wide receivers. Ohio State is in a nickel look with five defensive backs, but strong safety <player idref=t is moving toward the line at the snap to effectively serve as a linebacker. The key players for the Buckeyes are on the short side of the field: Defensive end Adam Bellamy, inside linebacker Etienne Sabino and outside linebacker Ryan Shazier. For Michigan, the key block will come from left guard Michael Schofield.

At the snap, the rest of Michigan's offensive line (sans Schofield) blocks down, including right tackle Mark Huyge (No. 72), leaving Bellamy unblocked. Toussaint is immediately showing a sweep to the right, with Schofield and Hopkins leading the way:

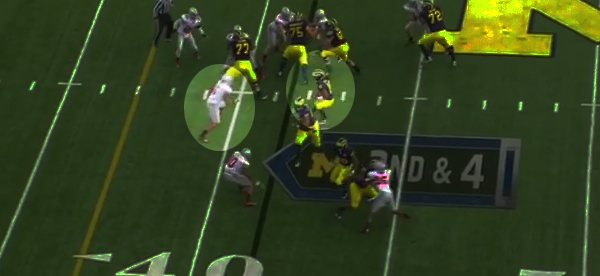

By the time Robinson carries through the fake handoff to Toussaint, Bellamy, Sabino and Shazier are flowing wide in response to the sweep action; meanwhile, the rest of the OSU defensive line has been successfully walled off:

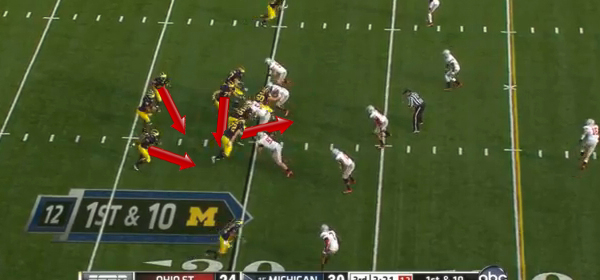

…leaving Robinson with a gaping seam to run behind Schofield's kick-out block on Bellamy, Huyge's downfield block on Bryant and Hopkins' edge block on Shazier. Sabino, unblocked, has simply overrun the play in pursuit of Toussaint:

And resulting in a 22-yard gain for Robinson, right up the middle:

The same basic play also worked for a long touchdown run from midfield (see below), a short touchdown run from inside the OSU 10-yard line and several steady gains throughout the game. When it's going that well, it can also serve as the basis for any number of wrinkles, from triple option looks to play-action passes:

The running game in general and the misdirection in particular took a hit Friday morning when coach Brady Hoke finally confirmed that Toussaint won't be making the trip to Dallas as punishment for a DUI arrest. With Touissant in the lineup, Michigan is the only team in the nation with two returning 1,000-yard rushers in the same backfield, and Alabama has another reason to risk sneaking its safeties closer to the line of scrimmage. Without him, Michigan has no proven running threat besides Robinson, who already has a big enough target on his jersey as it is.

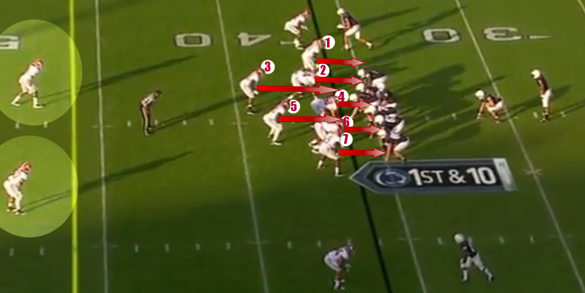

Counterpunch. Nick Saban is known for an endless array of zone blitzes and other pressure looks, but as Saban explains it, 'Bama's base 3-4 defense is essentially designed around basic gap assignments against the run — that is, the defensive linemen and linebackers are all responsible for shutting down a specific lane, without requiring an eighth man "in the box." Against a conventional two-back, two-receiver set, that's seven men, seven gaps and two safeties unencumbered to react to run or pass:

On the back end, the Crimson Tide can go to zone or man-to-man with their physical corners, but stopping the run up front is still very much a mano-a-mano proposition, one most defenses don't have the luxury of considering: To afford the extra man in the secondary, the front seven must consistently win one-on-one battles against blockers at the point of attack to clog up running lanes. Last year – and for most of the last four years – Alabama was better at that than any other defense in college football, leading the nation against the run in terms of yards per game (72.0) and per cary (2.4). Opponents managed to score three rushing touchdowns all season, two of them with the score already well out of hand.

Michigan is a unique challenge for this defense, though – especially in the first game of the season – on two fronts. One, the Crimson Tide are breaking in six new starters, including both cornerbacks and both outside linebackers, and all six of the guys being replaced are currently on NFL rosters. Two, the SEC is not exactly a hotbed for spread offenses that lean on shifty quarterbacks out of the shotgun. The closest thing Alabama saw to Michigan in 2011, scheme-wise, was probably Auburn in the regular season finale, which presented a similar array of motions and misdirections and a part-time running threat, true freshman Kiehl Frazier.

Because Frazier was no threat as a passer (not just an unintimidating threat but no threat; he'd attempted just 10 passes prior to the Iron Bowl, two of which were intercepted) Alabama had no qualms about using its safeties in run support. Here, see Mark Barron (No. 4) and Vinnie Sunseri (No. 3) playing outside contain when Frazier keeps on the read option:

But the design is not what makes Michigan's offense or Alabama's defense special; every coach knows pretty much what Nick Saban, Kirby Smart and Al Borges know. But they do not all have Nick Saban, Kirby Smart and Al Borges' players.

For example. Here's Denard Robinson on an otherwise well-blocked play, encountering an unblocked linebacker, Sabino, at the point of attack thanks to a cornerback blitz that gave Ohio State an extra man in the box:

In this case, one-on-one, it's no contest: Robinson easily sidesteps the tackle and is off to the races for Michigan's first touchdown.

Now, here's Alabama linebacker Dont'a Hightower on a perfectly blocked play, with a 260-pound fullback between Hightower and Kiehl Frazier:

Again, it's no contest: At the point of attack, Hightower attacks the block, stops the fullback in his tracks in the hole and stones Frazier for about a yard.

Which is the difference between Etienne Sabino and Dont'a Hightower, and why the latter is now making a few million dollars as a first-round pick of the New England Patriots. But the two guy who'll be manning the inside roles Saturday night, senior Nico Johnson and C.J. Mosley, are both returning starters themselves who match Hightower's size and could very well match his position in next spring's draft. Alabama does not miss tackles.

But that also demonstrates the difference between defending Kiehl Frazier and defending Denard Robinson, whose outright speed and quickness in tight quarters can't be simulated on a whiteboard or by the scout team; he can make positive things happen even when the defense disrupts the designed play. As relentlessly disciplined as Saban's defenses tend to be, any mental lapses or sloppy pursuit angles from one of the youngsters could mean lights out.