Urban Meyer reopens auditions for Ohio State's version of the 'Percy Position'

"As we start (camp), we don*t have that hybrid 'No.*3' * that guy that can do it all," Meyer said.

Ohio State was untenably green on offense in 2011, and looked every bit of it on a weekly basis. It took half the season for the quarterbacks to reliably complete a pass, only then if you're using a very loose definition of "reliable." As preseason practices begin in earnest for 2012, this is a group still grappling with the fundamentals.

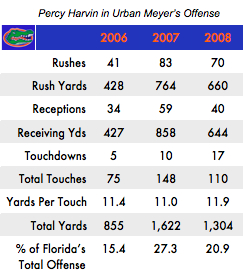

But in Urban Meyer's offense, the fundamentals happen to include a singular, specialized position personified by the player it was invented for, Percy Harvin, whose spectacular turn as a kind of hybrid wide receiver/tailback at Florida has convince Meyer to make the same dual-threat role a priority in Columbus. And why wouldn't he? In three years as a Gator, despite an assortment of hamstring and ankle injuries, Harvin racked up 194 carries for 1,852 yards (to save you the trouble, that's 9.5 per carry) and 134 catches for 1,929 yards, on teams that won two BCS titles and led the SEC in both total and scoring offense each of his last two seasons. I would ask you to name the last Division I player who went over 600 yards rushing and receiving in consecutive years, but there's not really a category for that.* In his last 15 games, Harvin scored 15 touchdowns. Any offensive coach would move heaven and earth to replicate that kind of production.

There's just one small caveat: So far, Ohio State's roster does not seem to feature Percy Harvin, nor the equivalent thereof. Which, as Meyer told the Columbus Dispatch, threatens to throw a minor crimp into his vision for the Buckeye offense:

"As we start (camp), we don’t have that hybrid 'No. 3' … that guy that can do it all," Meyer said.He’s talking about the way Percy Harvin played off the talents of quarterback Tim Tebow at Florida, helping the Gators win two national championships, or the combo of quarterback Alex Smith and back Paris Warren in 2003 and 2004 at Utah, where Meyer rose to national prominence.

[…]

"Those were perfect body types," Meyer said [of Harvin and Warren]. "Great acceleration, great speed, but also a toughness and strength to them where they can hit it inside."And if that type of player doesn't emerge in the next few weeks, it could stunt the development of the offense.

"I think stunt is the right word — you have to put the brakes on sometimes and say we can’t do that," Meyer said. "It's just the plays (that are drawn up); plays are good because of guys."

The first guy Meyer pegged for the "Percy Position" in the spring, tailback Jordan Hall, is still recovering from a nasty cut on his foot that required surgery in June, likely costing him at least the first two or three games next month. In the meantime, the reported candidates are returning receivers Corey Brown and Evan Spencer and incoming freshman Najee Murray, who is actually listed as a defensive back. There's also last year's leading receiver. sophomore Devin Smith.

The first guy Meyer pegged for the "Percy Position" in the spring, tailback Jordan Hall, is still recovering from a nasty cut on his foot that required surgery in June, likely costing him at least the first two or three games next month. In the meantime, the reported candidates are returning receivers Corey Brown and Evan Spencer and incoming freshman Najee Murray, who is actually listed as a defensive back. There's also last year's leading receiver. sophomore Devin Smith.

Returning to Meyer's central premise, though, plays are good because of guys. And at the moment, there are only a handful of guys at best playing college football – Clemson's Sammy Watkins, Oregon's De'<player idref=, maybe Tavon Austin in West Virginia – who have demonstrated anything remotely resembling Harvin's paralyzing combination of deep speed as a receiver andbetween-the-tackles instincts as a tailback. As it was executed at Florida, the job of the "No. 3" guy is to force defenses to respect his ability to beat them downfield, then exploit the subsequent numbers advantage in the running game when defenses overplayed the pass. Athletes who can consistently do one or the other are rare, coveted specimens; athletes who can consistently do both from the same place on the field are virtually unheard of. What if there was never really a "Percy Harvin Position" at Florida, so much as there was just Percy Harvin?

Consider Harvin's best play at Florida, a traditional counter off of pre-snap motion from the slot into the backfield, which was based entirely on what Meyer described as "the best first step I've ever seen." Not only was the defense forced to adjust on the fly from a spread passing formation to a power running formation; once the ball was in Harvin's hands, it had to deal with an abrupt, against-the-grain cutback beyond the grasp even of most Division I tailbacks:

Counter plays accounted produced by far the two longest plays of the 2008 BCS Championship Game against Oklahoma, the first a death-defying, 45-yard sprint by Harvin out of his own end zone in the first half, the second a 52-yard run that set up the Gators' go-ahead field goal in the fourth quarter. Harvin made these plays – this specific play – not on quite a routinebasis, but certainly with some regularity. While also, oh by the way, serving as the team's leading receiver.

After Harvin's exit for the first round of the draft, Meyer talked openly in 2009 about filling the same role with any number of blue-chip candidates on Florida's roster who could run step-for-step with Harvin and, in the cases of tailbacks Jeff Demps and Chris Rainey, had already flashed plenty of big-play chops in their existing roles. But no Gator even came close to matching Harvin's overall production that fall, and even with Tebow being Tebow at quarterback, the offense as a whole dramatically regressed. The following year, minus Harvin, Tebow and his longtime offensive coordinator, Dan Mullen, Meyer watched the offense and the rest of the operation begin to crumble and decided he'd seen enough. No one else in college football in the last decade, not at Florida or in any of Meyer's previous stops or in Mullen's subsequent takeover of Mississippi State, has simultaneously functioned as both a full-service tailback and wide receiver.

The more Meyer talks about his new team, in fact, the more it sounds like the really special talent on offense isn't going to be a skill player at all, but the quarterback, sophomore Braxton Miller, whom Meyer has repeatedly called "the most dynamic athlete I've ever coached." That may be hyperbole, but maybe not by much, as anyone who watched Miller's progress from a wide-eyed, scattershot apprentice to a real, live Big Ten quarterback in the span of about two months last year should be able to attest. In September, Miller was half of one of the most hapless quarterback duos ever assembled in losses to Miami and Michigan State, a young passer so overwhelmed by legitimate defenses that a 1-for-4, 17-yard afternoon in a win over Illinois was taken as a sign of progress. A week later, he was ad-libbing a Hail Mary to beat the best team on the schedule. By the end of the year, he was accounting for 335 of the Buckeyes' 372 total yards and three of four touchdowns in a tooth-and-nail shootout at Michigan.

Now, he gets to spend the next three years under a coach with a consistent track record for building dominant offenses around dual-threat quarterbacks with Miller's exact skill set. He's not Tim Tebow in short yardage, but based on the runaway success of Meyer's spread-option attack at Bowling Green and Utah before Tebow, Harvin and Co. went Medieval on the SEC, there hasn't been a scheme in college football in the last decade better suited to Braxton Miller. And there won't be many quarterbacks in college football over the next three years better suited to Urban Meyer. If he somehow uncovers a hidden gem on the roster with a comparable skill set to one of the most versatile, explosive players in recent memory, it's going to be one hell of a show. But it is not at all clear that he really needs to.

- - -

* There's no category, but the answer to the last player who went for at least 600 yards rushing and receiving two years in a row is Texas Tech's Taurean Henderson in 2002 and 2003, though it took him way, way more touches than it took Harvin. In fact, since Harvin left for the NFL in 2008, the only player who's joined the 600/600 club even once is Houston running back Charles Sims, who did it as a freshman in 2009. Last year, Oregon's Harvin-esque star, De'Anthony Thomas, was just five rushing yards away from breaching the 600/600 as a true freshman, and will almost certainly obliterate it in the next two.