Indiana is knocking on the door of America's greatest sports stories -- and the legends are watching

Indiana football is one win from a place usually reserved for miracles, movies and legends

Indiana stands one win away from a transformation once reserved for legends and the movies that borrow from them.

Two years ago, the man who writes those Hollywood scripts sat inside the Hoosiers' Memorial Stadium with an extra ticket in his pocket and an empty seat beside him, unaware he was witnessing the final stillness of yet another losing season before belief came home to Bloomington.

Angelo Pizzo, the screenwriter behind the sports film classics "Hoosiers" and "Rudy," is a lifelong Indiana fan, season-ticket holder and alum. As a kid, he attended countless Indiana football games with his father, making the one-block walk from his home to watch the Hoosiers be bludgeoned by the Big Ten's blue bloods. The stadium was nearly empty every Saturday.

On Monday night, he will trade one of the most coveted tickets in college sports history for a seat inside Hard Rock Stadium, where Indiana will chase the final step of a miracle journey from doormat to undefeated national champion, a season begging for a Hollywood ending.

"Forget about movies for this moment," Pizzo said. "It's a unicorn. I don't think there's anything like it."

He may be right.

Indeed, Indiana is doing something college sports have never quite seen before.

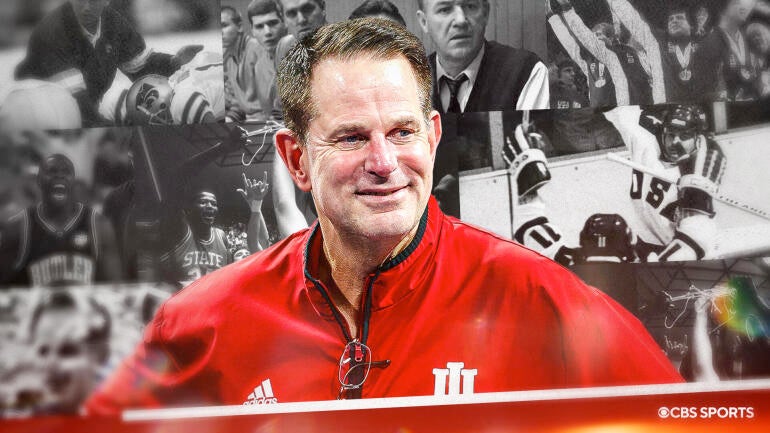

The No. 1 Hoosiers are an incredible 26-2 over their last two seasons, a breakneck turnaround not even second-year coach Curt Cignetti envisioned when he inherited a 3-9 team with only 40 scholarship players remaining on the roster. As recently as November, Indiana still owned the losingest record in college football history, but that flipped when Northwestern lost its 716th game on Nov. 8 and Indiana kept winning.

Indiana is 15-0, a Big Ten champion, and fresh off a jaw-dropping blowout of Oregon in the College Football Playoff semifinals at the Peach Bowl. A win over No. 10 Miami (13-2) would make Indiana the most out-of-nowhere national champion the sport has ever produced.

Would it transcend football?

"So now I'm a sports historian?" Cignetti deadpanned. "That's for you guys to figure out."

"I don't think there's anything that compares to this, even if they don't win Monday night," said legendary broadcaster Sean McDonough, who will call the championship game for ESPN Radio. "It's already unique in the history of college football for sure."

America will be watching. And so will the people who lived the greatest sports moments this country has ever produced. From the "Miracle on Ice" to Jimmy V and NC State's unforgettable run in 1983 to the architect of college football's greatest rebuild, they'll all be watching, waiting, hoping to see history once again.

"I can't wait to watch the game because I know how hard these players work and the sacrifices both teams made," said Mike Eruzione, who scored the decisive goal against the Soviets in 1980's "Miracle on Ice" Olympics victory for Team USA's hockey team. "You want to see that person who nobody believes in win. That's what makes our country so great. They embody what our country is all about: people overachieving and accomplishing great things."

The man who never blinks

Cignetti remains unmoved. He usually is.

He only cracks a smile -- and a beer -- after wins, but his laser-focused demeanor has turned him into today's most recognizable face on the sidelines.

People laughed two years ago when he was introduced at an Indiana basketball game and declared: "I've never taken a backseat to anybody and don't plan on starting now. Purdue sucks! But so does Michigan and Ohio State!"

On Saturday, Cignetti said it was a litmus test. "I knew I was out on a limb. I had to find out if the fan base was dead or on life support."

It wasn't.

It didn't take long for the fans to show up in droves and for Cignetti to turn the program around, leading the Hoosiers to the College Football Playoffs in his first season, ending with a loss to Notre Dame in the first round. When he lost several starters, including his quarterbacks, skeptics proclaimed that 2024 would go down as a fluke. Instead, Cignetti added Cal transfer Fernando Mendoza, who won the Heisman Trophy in December, and Indiana improved in nearly every statistical category while beating 10 opponents by 24 points or more.

This wasn't luck. It was programming.

When hope arrives

James Bomba, a reserve tight end for Indiana, understands better than most.

A third-generation Indiana player and Bloomington native, Bomba grew up steeped in Crimson and Cream. His father, Matt, and both grandfathers played for Indiana. His family stories stretch generations deep, including one about "Grandpa Bomba," a team doctor, saving "Grandpa Van Pelt" at a party and quietly covering up an injury.

James Bomba started his career on Indiana's 2-10 team in 2021, when all seemed lost under then-coach Tom Allen. Two years later, Cignetti arrived and everything changed overnight. "We've kinda skipped the whole section of what it takes to be great," he said with a laugh.

His mother, Kelly, an associate athletics director for Indiana, texts him after every win. James always asks how his father is feeling. "Dad won't stop laughing. He's cracking up," Bomba said. "He can't believe it, honestly."

Neither can the son.

"I haven't really felt too emotional, and I think it's because Cig has us all programmed," James said. "It's all about this week, practice, we're playing this game and then it's on to next week. It's always a 1-0 mindset. I haven't really felt the feelings I thought I would feel. You grow up, and you dream about winning a Rose Bowl. You win it, and it's like, I was happy, but then it's, all right, next game. It's been hard to realize, for sure."

When history runs out of comparisons

The Hoosiers just don't blink. They have been a machine in the postseason, drilling Alabama 38-3 in the Rose Bowl and Oregon 56-22 in the Peach Bowl. They rank in the top two nationally in both offense and defense, the epitome of an elite, balanced team. They rarely make mistakes, committing the nation's second-fewest penalties, and they're fundamentally sound to the point of irritation, leading to only a few missed assignments and tackles.

Tony Barnhart has covered college football for 50 years. The scribe known as "Mr. College Football" is in his final season, and his retirement tour coincides with Indiana's ascent. He's searching for language that doesn't quite exist. Fittingly, one of the greatest stories of his lifetime could come to fruition on his final night in the press box.

"People are having a hard time wrapping themselves around the fact that Indiana's not doing this with smoke and mirrors," Barnhart said. "They're not doing it with some exotic offense. They're really good, they're really well coached. You have to talk about them in terms of being one of the greatest teams ever."

If Indiana completes the fairytale with a Hollywood ending by beating Miami, Barnhart said he would take it one step further. A 16-0 Indiana team, the first in college football since 1894, would eclipse most comeback tales.

"You've got to think about them in terms of the 'Miracle on Ice.' It's that kind of level of comparison that I'd have no problem agreeing to."

Rebuilding is hard. Rebuilding a program that has been on the low rung for most of the last 100 years is supposed to be impossible. Turning it over in the blink of an eye, like Cignetti accomplished at Indiana, has never been done, but there are working blueprints sprinkled throughout history.

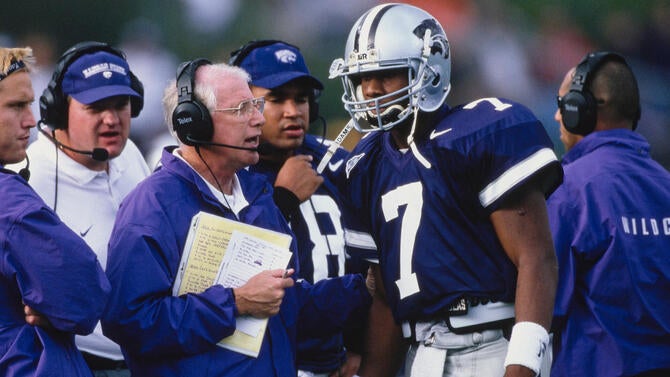

Bill Snyder took over a hapless Kansas State program in 1989 with only four winning seasons in its previous 44 years. By his third year, he won seven games, sparking a 27-year career that included 18 winning records, two Big 12 championships and seven 11-win seasons, including four in a row in the late 1990s. The flip from bottom dweller to championship contender led former Oklahoma coach Barry Switzer to label Snyder "the coach of the century."

"In some ways, it was an impossible task, and in other ways it was far easier than anyone could anticipate," the 86-year-old Snyder said this week.

The common ingredient in changing the trajectory of a losing program is changing the team's mindset, convincing others that the wins will come if they just put their heads down and work, Snyder said. At Indiana, Cignetti instilled the same singular focus.

"We tried to promote that it's to be expected," Snyder said. "If we apply ourselves and do things that we're asking, these things will happen. And when they happen, we don't expect anybody to be surprised. We want to feel comfortable that if we did the right things, this would come, this too would happen."

It's an echo from every past successful rebuilding project, and none was more dramatic than what Snyder accomplished at Kansas State -- until Indiana arrived on the scene.

"It's excellent for college football, for college athletics," Snyder said. "It's a value for anybody and everybody to know there's always an opportunity and there's always a chance. Good things can always happen."

Why underdogs don't think they're underdogs

They were what you call a "Cinderella."

NC State's run through the 1983 NCAA Men's Basketball Tournament has long been frozen in celluloid, punctuated by Lorenzo Charles rising above the rim to catch Dereck Whittenburg's desperate heave and flush it home for a 54-52 win over Houston. The images never fade. Jim Valvano sprinting aimlessly across the floor, searching for someone to hug. Teammates surrounding Charles beneath the basket. Every March, those clips resurface, stitched permanently into the fabric of American sports memory.

But to Whittenburg, it was never a miracle.

"No. You know why? Because we thought we could do it. We thought we'd be here," he said.

That certainty began with Valvano, who told his players from the first day they arrived on campus that they could win a national championship. Not dream it. Not chase it. Win it. Whittenburg hears echoes of that same voice today in Bloomington.

"He's got a little bit of NC State blood in him," Whittenburg said.

He's not wrong. Curt Cignetti spent seven seasons on Chuck Amato's staff at NC State, helping engineer a school-record 11-win season in 2002 before joining Nick Saban's first Alabama staff in 2007.

Belief matters, and often outsiders are the last to recognize it.

Another college team in Indiana ran headlong into that skepticism in 2010, when Butler's basketball team pushed through the NCAA Tournament to reach the national championship game against Duke.

Forward Gordon Hayward and guard Shelvin Mack knew they had a chance to be special heading into the season. The realization came that summer, when both played on Team USA's U19 basketball team and kept beating the 21-and-older team.

"We had that confidence and knew what it takes to get to the next level," Mack said. "We brought it back to our team. It felt like a regular game. We kinda expected to be there at that point. When Gordon was on the team, we knew we were special."

Led by coach Brad Stevens, Butler won 25 straight games. The Bulldogs played the Final Four just six miles away from their campus in Indianapolis, beating Michigan State 52-50 to advance to the championship. Comparisons to Pizzo's "Hoosiers" followed naturally: a small school, an unassuming roster, a sudden collision with destiny on the sport's grandest stage.

The difference was heartbreak. Hayward -- Butler's version of Jimmy Chitwood -- launched a half-court heave at the buzzer that rattled off the backboard, kissed the rim and tumbled to the court, inches from immortality.

"It would have changed the landscape of basketball," Mack said. "It's always these what-if moments you think about. I get that question a lot. I'm pretty sure we'd have a few movies by now. Just like the movie Hoosiers."

NC State's run 43 years ago was a Cinderella moment, but some forget the Wolfpack ranked in the top 15 before Whittenburg broke an ankle and missed the next 14 games. They went 8-6 in the ACC, but won the next nine games spanning across the ACC and NCAA tournaments to win those titles with Whittenburg back on the court.

"I've been in that zone where [the players] believe in what they do and their coach so much that they're playing for each other," Whittenburg said. "They know they can't make many mistakes. More than likely, they're not as talented as some of the other teams, but they are a better unit because they're all on the same page. There's no rocket science about what Indiana is doing. Cignetti is an old-school coach. He simplifies things."

NC State hasn't won a national championship since that night in 1983, which only sharpens its place in memory. Yes, they were underdogs. But it was how they won that elevated the moment into legend.

Indiana can claim that same ground Monday night.

"They'll be lauded, unless there are five more after this one," said Ernie Myers, the freshman guard who stepped into Whittenburg's starting role while he was injured in 1983. "These guys' lives are going to change dramatically. They'll never forget you. You'll eat for free for a little while. It's just unbelievable. I've gotten jobs because they found out I was on that '83 team. Put it on your resume and they'll talk to you".

Hoosiers II

If the moment arrives and Indiana wins, college football will shift, and so will the lives of the Hoosiers' players. Plucky programs with no prior history of championship success in the modern era are not supposed to suddenly emerge and win national titles. The sport hasn't crowned a first-time title winner since Florida in 1996.

Yet here Indiana stands, unfazed, staring into territory the program has never known. Cignetti's team moves with the same single-minded focus as its coach, who demands precision in every rep, every snap, every moment. The nerves will come, and so will the butterflies. Every great figure in American sports history has felt them.

"Embrace it. Love it," Eruzione said. "It's a great challenge. You can't hide, you can't shy away from it because it's there. You can't be afraid to go out and play. In the Soviet game, I wasn't afraid. I was nervous, I was curious, I was anxious. I couldn't wait to play the game and find out. That's when you rely on your teammates. That's when you rely on all those practices during the year with coach Cignetti.

"This didn't just happen overnight. This has been a process that started with camp. It's been a grind, a long season of hard work and dedication and team meetings, overcoming injuries. All the little things that are so important for a team coming together. So I'd look at it as, 'hey, guys, this is going to be fun.'"

It might also be legendary. The type of story you only see in the movies. Even Cignetti dropped hints after the Hoosiers' first-round win at the Rose Bowl.

"It would be one hell of a movie," he told ESPN's Rece Davis on national TV.

As you might imagine, the screenwriter in Bloomington's phone lit up like a Christmas tree. Pizzo's friends asked him over and over if he had started writing the script for "Hoosiers II."

"At this juncture, it's really impossible to step back and think about it as a feature film," Pizzo said. "The reality is so present and so visceral, you couldn't recreate it on the screen. Especially so soon after it happened."

Still, what a story. Every Indiana fan has one to share during this run, even Pizzo, who last year was introduced to Cignetti by athletics director Scott Dolson at an alumni event -- and immediately sensed something different was happening in Bloomington. They exchanged a perfunctory handshake, and Cignetti looked at him dead in the eyes.

"I've never seen 'Rudy' and I never will. I hate Notre Dame," the coach said, Pizzo recalls.

Pizzo laughed. Cignetti did not. Then he winked and tapped Pizzo on the shoulder.

"But people tell me it's pretty good."

Indiana has a history of winning, just not in football. The Hoosiers won five basketball national titles, including three under the late Bob Knight, who Pizzo befriended in the late 1980s. Pizzo even skipped Hollywood's Oscars ceremony in 1987 to watch the Hoosiers defeat Syracuse 74-73 for Knight's final title. Pizzo isn't skipping this game. He'll be there in person.

"It would trump any national championship for basketball," Pizzo said.

It would also ripple far beyond Bloomington -- everywhere except, perhaps, Miami -- and lift the Hoosiers into rarefied air, perhaps eclipsing the sport itself.

"Indiana has become America's team in a way, because they do represent the player or person who most people think of in terms of themselves," Pizzo said. "That's why 'Rudy' has sustained in popular culture for as long as it has, because it goes beyond sports. It's really about the average guy who punches above their weight.

"It's not like a welterweight knocking out a light heavyweight. This is a lightweight knocking out heavyweights one after another, after another."