Oversigning Index: On another front, it's still Alabama and everyone else

Even after a concerted crackdown on "oversigning" by the SEC over the past three years, no coach in any league overshot the mark this year with as much gusto as Nick Saban.

Saban must trim Alabama's roster by at least 10 players to adhere to the NCAA's scholarship cap. (US Presswire)

Last week, four Alabama players were arrested on felony charges, suspended indefinitely from the team and barred from campus. In Tuscaloosa, the news prompted opposite reactions.

Per standard protocol, Crimson Tide fans braced themselves for a tidal wave of schadenfreude, inevitable taunts of "Parole Tide!" and the early lead in the Fulmer Cup. At the same time, though, there was virtually none of the usual handwringing over the impact to the depth chart. This time, the offenders were utterly expendable, for reasons that had nothing to do with the fact that they happened to be backups: Not only can the defending BCS champs afford to lose a handful of potential contributors in one fell swoop, but more so than any other major college football team this spring, it actually needs to. After adding 26 new names to the roster earlier this month -- and landing again in its familiar spot atop the national recruiting rankings -- Alabama is the most oversigned outfit in the nation.

That should come as no surprise, given that Bama has consistently (and legally) operated on the edge of NCAA scholarship caps throughout Nick Saban's tenure. Ostensibly, teams are limited to 85 scholarship players on the roster at any given time. In practice, because the NCAA doesn't do a head count until the start of preseason practice in July or August, sometimes long after incoming freshmen and other newcomers have already arrived on campus, coaches can cross the line on national signing day as long as they're able to come in under the cap six months later. Yet even after a concerted crackdown on "oversigning" by the SEC over the past three years, no coach in any league overshot the mark this year with such gusto.

Eddie Lacy is one of 12 departing scholarship players from Bama's 2012 roster. (US Presswire) |

Alabama wasn't very far from the line to begin with. The Crimson Tide only lost a dozen scholarship players from last year's unusually young BCS championship team, including three early departures for the NFL and a former walk-on (long snapper Carson Tinker) who was awarded a scholarship before last season, leaving them with at least 70 scholarship players scheduled to return in 2013 and a maximum of 14 available openings. Still, on signing day, Bama added almost twice that number -- including, yes, a two-star prospect from California, Cole Mazza, who is projected strictly as a long snapper. Few other schools had so few slots to fill, and the ones that did did not come close to overshooting the mark by such a distance: Relative to the competition, Saban and his staff effectively recruited as if scholarship limits do not exist.

Of course they do exist, and one way or another Alabama must toe the line by the start of preseason practice like everyone else. That can happen any number of ways, and already has: One of the 26 signees in the new class, three-star offensive lineman Bradley Bozeman, has already agreed to "grayshirt," or delay his enrollment until 2014 so as not to count against this year's scholarship cap; a few of his more touted classmates will probably be forced to follow suit. One or two others may fall short academically. As we've already seen, legal and disciplinary issues can unexpectedly thin the ranks overnight. Inevitably, some veteran backups will read the writing on the wall and decide to transfer some place with a more accommodating depth chart.

If all else fails, it comes down to making cuts, preferably in a fashion that doesn't involve actually having to say, "you're cut," which Saban adamantly denies he has ever done. The first to go are usually fifth-year seniors who are unlikely to contribute, a relatively uncontroversial move as it's common at many schools for veteran backups to bow out quietly after four years with a degree in hand. (Alabama has several candidates for this path, most notably linebacker Jonathan Atchison and defensive linemen William Ming, Anthony Orr and Chris Bonds, all members of the 2009 recruiting class who have yet to earn a letter.) Injured players may be asked to accept a medical hardship, which allows them to remain on scholarship without counting against the cap but effectively ends their career, even if the injury is not necessarily career-ending. (Saban has been criticized in the past for using the hardship more than any other coach, and by players who said they felt pressured to accept a hardship. At least one player who was released for medical reasons has gone on to play at another school, albeit on a much lower level.) Though all transfers are technically voluntary, some may come with a tacit endorsement from coaches -- only looking out for the player's best interest in getting on the field, naturally. Asking an incoming recruit to delay enrollment after he's signed a letter of intent is a last resort. But whatever it takes, there is no way around the fact that somewhere in the vicinity of a dozen players currently slated to wear the Crimson Tide uniform this fall will be culled from the roster over the next six months.

(For the record, here is a complete breakdown of Alabama's current roster by signing class, including incoming recruits in the class of 2013 and the four recently arrested players -- Brent Calloway, Tyler Hayes, D.J. Pettway and Eddie Williams -- who have been suspended from the team but not dismissed.)

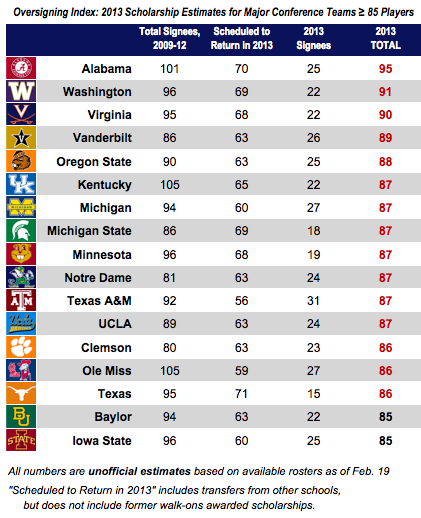

No other team is facing that level of inevitable, automatic attrition. The closest to Alabama, numbers-wise, is Washington, which also lost just 12 scholarship players from last year's roster but just signed 22, bringing its unofficial scholarship count to at least 91 (not including any former walk-ons who may have earned scholarships). Among teams from the "Big Six" conferences with automatic BCS bids, current rosters indicate Virginia (90 scholarship players), Vanderbilt (89) and Oregon State (88) also have some relatively intensive trimming to do between now and August:

Assembling those numbers is not only a time-consuming exercise: It's also a quixotic one, no matter how meticulously researched, amounting to a fleeting snapshot of living organisms in a constant state of flux. Walk-ons, medical hardships and other vagaries are not easily accounted for.

In general, though, it's fair to say that recent rules changes targeting oversigning have largely paid off, especially in the SEC, whose members once dominated the genre to an extent that is no longer true across the conference as a whole. Every team beneath the top two or three on that list is well within the range of "natural" attrition, and most of them will probably end up a little below the cap once grades, legal issues and injuries have taken their toll. In several of those cases -- see Michigan, Notre Dame and Texas, for sure -- the more obsessive factions of the fan base can already predict which fifth-year seniors are likely on their way out. Oregon State has enthusiastically embraced the grayshirt under coach Mike Riley. Kentucky, now under the watch of first-year head coach Mark Stoops, can expect the usual exodus that tends to follow the arrival of a new staff. Spring practice is a reliable filter for players who fail to make a move on the depth chart and opt for a transfer.

So outside of Tuscaloosa, it looks like business as usual. No, scratch that: Inside Tuscaloosa, it looks like business as usual, too. Nick Saban is just running his business on a slightly different scale.