Jim Harbaugh strongly believed that if and when it became legal to pay college football players, Michigan would benefit.

Knowing the significant wealth emotionally invested in seeing Michigan football succeed, the then-Michigan head coach believed the Wolverines would have an advantage over the SEC schools he loved to poke at over the years, from his barn-storming satellite camps tour to comments that all but accused the southern schools of cheating.

Michigan had a long list of wealthy benefactors to choose from including Miami Dolphins owner Stephen Ross and former Mets owner Fred Wilpon.

"He reasoned it could only benefit Michigan if it became legal to share some of the spoils with the athletes," said Todd Anson, long a Harbaugh consigliere and a Central Michigan University trustee. "That was the impetus for him asking me to form a collective, which I did. Jim even named it for me TWT -- 'The Winningest Team.'"

The goal was to build a privately funded $250 million war chest that would, in Harbaugh's words, wake the sleeping giant that is Michigan athletics. Anson says he even approached Google co-founder Larry Page, a Michigan graduate, about funding TWT. The world's sixth richest man ($155.7 billion per Forbes) wasn't interested in sports and it never gained much traction.

Harbaugh's dream never came to fruition during his time at Michigan, though he did of course ride off into the sunset with a national championship after the 2023 season, but his belief in the advantages his alma mater would have in this new world have begun to take place.

Page may not have been interested but Michigan reeled in an even bigger fish: Larry Ellison, the fourth-richest man in the world with a net worth north of $200 billion, according to Forbes.

The Oracle co-founder had no obvious ties to Michigan and even attended a different Big Ten school (Illinois). It's why so many were caught off-guard when the Champions Circle, a Michigan-related NIL collective, thanked Ellison and his wife Jolin for their help in Michigan landing No. 1 overall 2025 recruit Bryce Underwood, who had been committed to LSU.

Barstool founder Dave Portnoy, a Michigan graduate who previously proclaimed he'd pay $3 million for a top quarterback, later said he was involved in the process and that Jolin, who attended Michigan during the Brady Hoke era, refused to suffer through mediocrity again less than a year removed from the Wolverines winning a national championship. Portnoy has said Jolin told him she couldn't "stomach waking up on a Saturday knowing that we're not the best team on the field" and wanted to "stack" national championships.

Michigan will have to wait at least a year to stack championships, as Jolin hopes, but the Big Ten as a whole has a chance to do so Monday night when Ohio State takes on Notre Dame in Atlanta, the heart of SEC country. If Ohio State wins, it will be back-to-back titles for the conference with considerable reason to be bullish about the Big Ten's future prospects.

Conversely, it marks the first time since 2004-05 that the SEC won't play for a national championship in back-to-back seasons, a bookend to a dominant run of 13 national championships over the last 18 seasons.

Is this a new, or at least more balanced, era?

The SEC isn't exactly floundering. But by any reasonable measure – a standard the conference has set – the SEC has been down the last two years. By early November, 13 of the league's 16 teams had at least two losses.

The Big Ten stepped up, leading the country with four teams in the first 12-team playoff. Indiana became a national story. Oregon earned the No. 1 seed. Ohio State and Penn State both made the semifinals, with the Buckeyes having a chance to reign supreme over the sport next week.

"I don't see any trophies in their [Big Ten] trophy case with dollar signs for being the wealthiest conference," said one sports media analyst.

There may not be banners for generating the most revenue but in this current era of college football, financial resources are paramount and no one has more of them than the Big Ten. In the current media rights deal with NBC, CBS and Fox, Big Ten schools will be making an average of $100 million annually in media rights alone when the current deal expires in 2030. The SEC is expected to top out at $75 million.

"We're now moving in an era of deregulation and House settlement where your ability to perform and compete at the highest level is largely predicated on resources," Oregon athletic director Rob Mullens told CBS Sports. "We're all doing everything we can to identify additional resources and when you're in a league that has an outstanding media rights deal with incredible distribution and you can play – I think we played seven straight weeks on network TV and had outstanding ratings.

"When you're a national brand, people can connect to it that way and it allows you to have an audience of more interested people. As we're trying to create additional resources, that's extremely helpful."

The rivalry between the Big Ten and SEC began long ago. Those two conferences are physically, financially and in a recruiting sense, dominant.

In 2007, former Big Ten commissioner Jim Delany posted what was called an "open letter" on the conference's website. The letter laid bare what stereotypes had been established over the years -- that the Big Ten was a high-brow, academic league that did it the right way and the SEC was a bunch of renegades.

"I love speed and the SEC has great speed, especially on the defensive line, but there are appropriate balances when mixing academics and athletics," Delany wrote.

He added: "Not every athlete fits athletically, academically or socially at every university. Fortunately, we have been able to balance our athletic and academic mission so that we can compete successfully and keep faith with our academic standards."

Then-SEC commissioner Mike Slive was incensed. There weren't any innocent parties. Delany oversaw the conference during the Fab Five scandal at Michigan. Academic giant Northwestern had been caught in two point-shaving scandals.

Meanwhile, Slive was in the process of polishing the conference, seeking to have every school off probation. It worked. For a while.

A large part of the Big Ten success in the middle of the 20th century had to do with demographics. SEC schools didn't fully integrate until the 1970s. Meanwhile, there was significant migration of African-Americans from the Deep South to the Rust Belt.

From 1952-1968 the league won six national championships, three of them unanimously. Michigan State in 1952, Minnesota in 1960 and Ohio State in 1968 swept both the AP (media) and UPI (coaches) polls. Twelve times in those 16 years, Big Ten squads finished in the top two of one or both of the major polls.

Compare that to the current run by the SEC, which has won 13 out of the last 18 championships. Beginning in 2006, the SEC won an unprecedented seven consecutive national championships.

That run planted in the minds of voters, fans, computers and media – rightly so – that the SEC was the dominant conference.

"The Big Ten has not been as good with the narrative," Tony Altimore, a strategy consultant with Altimore Collins & Company told CBS Sports. "They've [SEC] really done a great job with conference support. They really pioneered the recruiting end better than anybody."

The population shift that helped the Big Ten in the middle of the century reversed. The SEC's run has coincided with a national trend of a population shift from northern states to the Sun Belt. Tech growth, favorable climate and a business-friendly environment all contributed to the shift. Over the past decade, the Sun Belt region accounted for 80 percent of the nation's population growth, according to Moody's.

When the Atlantic Coast Conference considered expansion in 2003, one of its TV advisors commissioned a study showing how the population in southern conference states was growing.

"People are not moving into Michigan. They're not moving into Wisconsin. They're leaving. They're moving South," said former Big 12 commissioner Chuck Neinas.

The population boom gave southern schools a recruiting advantage as Georgia, Florida, Louisiana and Texas annually produced a considerable amount of high-level talent. Prestige and tradition has always had a place in college football but it became easier to win at a place like LSU, once Nick Saban got everyone pulling in the right direction, than Nebraska, which dominated the sport under Tom Osborne in the 1990s but had a limited natural recruiting base.

Those recruiting advantages haven't gone away but this era has offered the cold-state schools up north an opportunity to minimize them with cold, hard cash.

Ryan Day generated huge headlines across the sport two-and-a-half years ago when he said at a booster event it'd take $13 million to retain the talent on Ohio State's roster.

It wasn't quite the shot across the bow of Nick Saban accusing Jimbo Fisher of buying his entire team a year earlier but it signaled to the rest of the sport it'd take considerable financial investment to win at the highest levels.

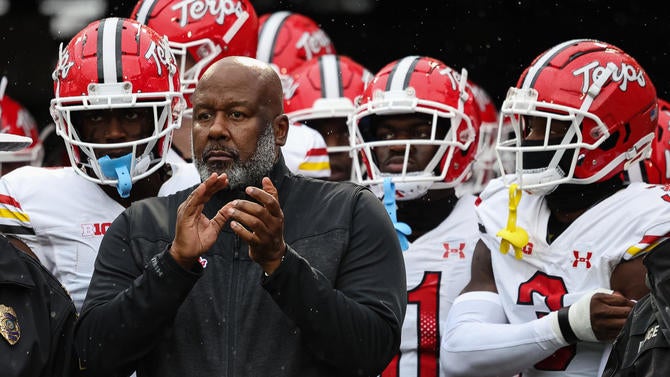

Fellow Big Ten coaches like Iowa's Kirk Ferentz said their schools would be in trouble if that's the financial commitment it'd take. Maryland's Mike Locksley said he'd be OK with half that number.

A lot has changed in the last two years.

"Right now look at the numbers, it's $20, $23, $25 million rosters," said Cardale Jones, the co-founder and general manager of THE Foundation, a NIL collective supporting Ohio State. Jones won a national championship with Ohio State in 2014, emerging from third on the depth chart to national stardom. Jones is currently a CBS Sports HQ college football analyst.

Ohio State spent at least $20 million on this year's roster, according to athletic director Ross Bjork, which is one win away from winning it all after a stupendous run of blowouts against Tennessee and Oregon and a win over Texas in the Cotton Bowl. Ohio State focused on retaining elite talent like Jack Sawyer and Emeka Egbuka for another year rather than head to the NFL while supplementing the roster with targeted needs. The Buckeyes went out and got a starting quarterback (Will Howard), starting center (Seth McLaughlin), starting safety (Caleb Downs) and a two-time all-SEC first-team running back (Quinshon Judkins).

"I think it was a situation where the coaching staff kind of foresaw a 12 months, 13 months from when they lost the Cotton Bowl to how special something could be and I think we're all seeing it unfold before our eyes," Jones said.

The numbers keep going up as a convergence of NIL money and future revenue share money has flooded the market and driven player compensation prices way up. Blake Lawrence, co-founder of Opendorse, recently told CBS Sports the numbers have essentially doubled during this most recent transfer portal window.

Pay-for-play is technically against the NCAA rules but they have not been enforced for nearly a year since Judge Clifton Corker granted a preliminary injunction against the NCAA saying it likely violated federal antitrust law and that athletes prevented from knowing potential compensation before choosing a school would be hurt.

After that ruling, the NCAA announced it would pause all enforcement-led investigations into NIL. There has still been no final outcome with the case – the NCAA recently filed its sixth extension request – allowing for schools, collectives, players and their representatives to be much more open in discussing NIL-related compensation without the fear of NCAA repercussions.

It has allowed for programs willing to aggressively spend to capitalize on the opportunity. It has also exposed an interesting wrinkle: In a pure money battle, the Big Ten is better positioned than the SEC and other conferences.

A super booster like Ellison or Nike co-founder and Oregon alumnus Phil Knight, the world's 52nd richest man with a net worth of $33 billion, is a massive advantage in this current unregulated recruiting world.

Stephen Ross, whose name adorns the Michigan business school and is worth $17 billion, is still "the first call everybody makes" when Michigan needs money, according to Anson. Ohio State has Bath & Body Works, Inc. co-founder Les Wexner ($7.9 billion) while Rocket Morgan co-founder and Cleveland Cavaliers owner Dan Gilbert ($23.3 billion) is a Michigan State graduate.

Meanwhile, the state of Alabama, which has dominated the sport in many ways, doesn't have anyone on the Forbes 400 list. Auburn trustee and avid fan Jimmy Rane is the richest Alabama resident with a net worth of $1.5 billion, according to Forbes.

When compared to the SEC, the Big Ten dominated the 2025 US News Best National University Rankings, with 16 of its 18 schools placing in the top 100, while the SEC had five. Seven of the top 10 schools with the most living alumni are in the Big Ten including Ohio State (No. 8).

With those big alumni bases come the accompanying huge stadiums to fit them all in. The Big Ten has the three largest football stadiums in the country – Michigan, Penn State and Ohio State. Meanwhile the SEC owns spots No. 4 through 13.

Through expansion, the Big Ten has cornered big markets like Los Angeles (USC and UCLA), New York (Rutgers), Washington, D.C. (Maryland) and Seattle (Washington). Those big markets plus the long-standing ones like Chicago, Detroit and Minneapolis give Big Ten schools fertile financial grounds to solicit donations, NIL deals and partnerships.

Of course, having the money is only half the battle. Those wealthy alums have to feel compelled to spend money on their alma mater's sports teams.

For instance, Google co-founder Sergey Brin is the world's seventh-richest man at $152 billion. Brin got his undergraduate degree at Maryland as his father, Michael, was a mathematics professor at the school. Like his Google cohort Page, Brin hasn't shown much affinity for college athletics but he has the kind of wealth that could transform his alma mater's prospects. Last year, Brin's parents, Michael and Eugenia, donated $27.2 million to the University of Maryland to endow the Brin Mathematics Research Center and Brin Endowed Chair in mathematics.

Maryland coach Mike Locksley said it was above his pay grade to reach out to Brin directly and fully trusted athletic director Damon Evans' fundraising efforts, but that he'd love to have a 30-minute conversation with him one day. He brings up Under Armour founder Kevin Plank and Barry Gossett, former chairman of Acton Mobile Industries, as two long-time generous supporters of Maryland athletics who have gone above and beyond to support the Terrapins. He hopes other wealthy alumni who benefitted from going to the school follow the lead of Plank and Gossett and feel compelled to give in this new era.

"We've got some (billions) behind our people that have come out of here," Locksley said in an interview last year. "It's just whether or not it's important to see the brand of Maryland do well."

That last part has always been an area SEC schools have excelled in. In college towns like Tuscaloosa, Oxford and College Station, nothing is more important than the local football team. Fans build their social calendars around it – no fall weddings is a common refrain – while gameday visitors juice the local economy. As cliche as the SEC's slogan may be, it rings true: "It Just Means More."

That passion will be critical moving forward in a House settlement world where ticket revenue, jersey sales, donations and other financial contributions will pay for the annual $20.5 million revenue share payment with that number going up each year moving forward.

The House settlement, if approved in April, would come with a component that would require NIL deals from boosters or collectives of more than $600 to be subjected to a fair market value analysis. In theory it could limit the big money NIL advantages of certain schools and is intended to return NIL to its original intentions of allowing athletes to capitalize on their likeness rather than a guise of pay for play compensation, but there is considerable skepticism within the college athletics ecosystem that it'll survive legal scrutiny.

"There's so many things that are wrong with it," said Brian Davis, founding partner of Forward Counsel. "Just in general a restraint on free trade needs to pass certain analysis and it doesn't come close. Who's to say what's fair market value and what isn't?"

Davis, who has represented numerous prominent college players during the NIL era, specifically points out the idea of a third-party clearinghouse rejecting an Oregon NIL deal from Nike co-founder Phil Knight, one of the greatest sports marketers in American history.

"Who are we to say he isn't spending his money wisely on a fair market value basis?" Davis said. "That's up to him to determine and he's done a damn good job in his career determining how to build a market."

Legal battles aside, the Big Ten is well-positioned to succeed in this version of college football. It will be difficult, if not downright impossible, for any conference to go on the run the SEC did over the last two decades with the way NIL and the transfer portal has dispersed talent around the country. There will be plenty of back-and-forths in the years to come on whether the Big Ten or the SEC is college football's best conference.

But on Monday night in Atlanta, with an SEC officiating crew on the field, the Big Ten has a chance to cap an incredible season with its second consecutive national championship. It could be just the start of a new world where the defining slogan could be "It Just Means More Money."

"When you look at the depth, the passionate fan bases, the media deals, all the outstanding leadership, all the elements that will enable you to remain as a premier conference in all of college athletics are there," Mullens said. "Now we just have to continue to collaborate, continue to have some foresight and make sure that we keep working our tails off."