Jaylen Brown is the first test case of the "max or bust" salary philosophy created by the new CBA

The new CBA has changed the way teams will allocate salary

Austin Rivers made waves this week when he criticized Damian Lillard's trade request, but in the process, he shed some light on a less glamorous but perhaps more significant problem facing the NBA today. "Our CBA deal that we just signed, and I don't even wanna get heavy into that, that thing is, don't even get me f****** started on that deal that we got going because it's top heavy," Rivers bemoaned. "That's why we're seeing all these teams right now, you either make $50 million or $2 [million]. It's the most lopsided contract, teams, it's a joke bro. I can't tell you how many mid-level guys are signing for the vet minimum around the NBA"

This was explicitly an outcome the NBA's new CBA was attempting to avoid. One of the league's primary goals in revamping its salary and luxury tax structure was to stimulate the middle class, both in terms of players and teams. The mid-level exception was increased as both a way to get free agents paid more and as a tool to encourage player-sharing. The rules governing salary-matching were loosened... but only on the lower end of the scale. Meanwhile, the prohibitive second apron was designed to force the league's priciest teams to make hard choices about who they keep.

And, to Rivers' dismay, those teams are almost universally choosing to keep their $50 million players. The Phoenix Suns currently have 15 players on their roster. Four of them are on max contracts and the other 11 are either on minimum contracts or, at best, Non-Bird deals limited to a modest raise upon a prior minimum contract. Their fourth-highest-paid player (Deandre Ayton) is making $32.5 million and their fifth-highest-paid player (Eric Gordon) is making $3.2 million. This is an extreme example, but not an uncommon one. The Warriors have five players above $20 million, but nobody else is earning eight figures. The defending champion Nuggets are currently allocating almost 87% of their total team salary to their starting lineup.

That new revamped non-taxpayer mid-level exception? A whopping three players used it to earn 2023-24 salaries that exceeded the maximum offered by the 2022-23 mid-level exception. Gabe Vincent topped it by a whopping total of $10,000. Donte DiVincenzo did a bit better, but did not earn the full mid-level exception. The only player that did this offseason was Dennis Schroder, who got just a two-year deal.

Meanwhile, just as Rivers claimed, the number of viable role players signing for the minimum is skyrocketing. Thus far this offseason, 18 players who played 18 or more minutes per game last season have signed for either the minimum or the 20% non-bird raise allowable off of a previous minimum. Most of them technically got two-year deals with player options for the second season, a minor concession that benefits teams from a public relations standpoint by making these deals look a bit bigger than they actually are. Starting-caliber players like Christian Wood and Kelly Oubre Jr. remain available, but current market conditions suggest they are unlikely to make more than the minimum when they eventually sign.

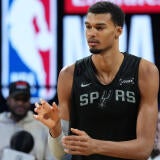

And those $50 million players on the other end of the spectrum? Well, Rivers undersold them. On Tuesday, Jaylen Brown became the NBA's first $60 million per year player when he signed a five-year, $304 million extension with the Boston Celtics. The deal was also the first $300 million pact in league history, but if the concept of "Jaylen Brown, highest-paid player in NBA history" seems a bit off to you, remember that the league's first $100 million player was Juwan Howard and its first $150 million player was Mike Conley. Timing is everything when it comes to milestone contracts. The raw numbers are almost irrelevant. This is what a max contract looks like today, and the Celtics deemed Brown a max player. What's far more interesting is what is happening to those between these two extremes: not quite max players, but far from minimums.

There's probably a gap between Jaylen Brown and Dejounte Murray, but it's not an especially big one. Murray has made one All-Star team and Brown has made two. Murray has an All-Defense nod and Brown does not. Over the past two seasons combined, Brown has averaged 4.3 more points per game while shooting two percentage points higher from the field (48.3% to 46.3%) and one percentage point higher from 3-point range (34.6% to 33.6%). Brown is the better player, but not by much.

But Murray will make half as much for the foreseeable future. Earlier in July, he inked a four-year, $120 million extension with the Atlanta Hawks. The consensus surrounding that deal was that it was surprising. Murray was limited by the NBA's veteran extension rules even if those rules were relaxed slightly by the new CBA. The expectation was that Murray would seek a richer deal in free agency next summer, when he would not have been limited and likely could have earned more even if he'd stayed with the Hawks. That he signed the extension anyway suggests that he was uncertain that he could do so.

It's a reasonable fear. Only one free agent changed teams for more than $25 million this offseason. That was Fred VanVleet, who went to the Rockets, the NBA's worst team over the past three seasons. Few teams hoard cap space anymore, and those that do aren't especially desirable destinations. Teams retain an enormous amount of leverage when players have nowhere to go. Just look at James Harden. He opted in to remain with a team he wants to leave because he simply had nowhere to go in free agency. Now he can't even get his preferred team, the Clippers, to pony up the assets it would take to trade for him. Teams will still go the extra mile for max-level players. The drop to anything less than that is growing steeper and steeper.

It's a market inefficiency teams are going to exploit. Boston and Phoenix have gone the top-heavy route. Would they have been better off, say, flipping Brown for Murray and the assets it would have taken to land Jerami Grant in a sign-and-trade with the Blazers? The salary cost would have been roughly identical. Boston has a top-10 player in Jayson Tatum to ease life on non-star, high-end players like Murray and Grant. Could players of that caliber survive without someone like that?

Someone is bound to try. There are going to be attempts at recreating the magic of the 2004 Pistons, and perhaps more contemporarily, the 2015 Hawks. If everyone else is building around two or three $60 million players and a bunch of minimum salaries, why not zag and grab six or seven players in the $20-30 million range? Such players are far more attainable. They're easier to keep in smaller markets. And right now, the value gap between them and their max counterparts appears to be smaller than ever.

None of this is to criticize Boston's decision to max Brown, of course. He's an All-NBA player. They just came five wins short of the championship. A year ago they were two wins away. Boston didn't need to break up this team yet. The true financial weight of this deal won't be felt for another two years, when both Brown's deal and Tatum's inevitable extension have kicked in and the Celtics really have to start making those hard choices about who they can keep. They can always trade Brown then.

But if Rivers is correct, they'll keep him and shed their mid-tier salaries. That appears to be the direction more and more teams want to go. Brown and the Celtics are just going to be our first real test case of what might be the new world we're entering. Keeping multiple max players has never been more costly. Only time will tell if it's worth the price.