Second chances in the Sunshine State: Coaches look to reboot careers in Florida

Four coaches with immense pedigrees look to sunny Florida for rejuvenation, not retirement

SOUTH FLORIDA -- Don't even try to figure out the geography. You won't find the boundaries on any map.

But there is a region here -- uncharted, invisible -- almost a new state of football in Florida. It would essentially take a 562-mile road trip to get across, over and around it.

It would take much longer to wrap your mind around its inhabitants.

From Tampa, down to Miami, over to Coral Gables and up the Gold Coast to Boca Raton -- within its borders are coaches owning a combined two Super Bowl rings, seven national championship rings and 10 SEC titles. For starters.

They are hardly beginners: Charlie Strong (South Florida), Butch Davis (FIU), Mark Richt (Miami) and Lane Kiffin (Florida Atlantic).

Total career wins: 298. Total combined years in their current job: one (Richt). If you don't know them because of redemption or a reboot, you certainly know them by reputation.

"They tried to keep him quiet and hidden down here," Brett Romberg said of Kiffin. Romberg is a local radio host and former Miami All-American. "It didn't take long for Lane to be photographed with a couple of ladies in a bar or two in Boca. I guess it didn't take him long to pound the pavement and get his feet wet down here."

This state of football is where tailback meets backstory -- some spicier than others.

Their stops aren't last chance saloons by any means. Richt, 57, is reimaging his career at about the same age that Bob Stoops, 56, is ending his.

Meanwhile, Davis returns to coaching as a senior citizen (age 65) after effectively being blackballed from the sport. Strong is looking to rebound after posting the worst three-year record in Texas history (16-21).

Kiffin, in his fourth head coaching job before his 43rd birthday, wants to be Nick Saban.

You read that right.

"I can do that, as crazy as that sounds," said Kiffin, fresh from a, um, colorful three-year run under Saban as Alabama's offensive coordinator. "Erase all that. Learn from those things. I'm so much more prepared to be a head coach than had I never had a job."

Going forward in this region, their lives and careers will be intertwined in some sort of way. Davis and Kiffin are in the same conference. Strong goes back to the state -- if not the region -- he knows best having spent 15 combined years at Florida and winning two national championships with Urban Meyer.

Under Richt, Miami just tied for the program's most wins (nine) since 2003. If that seems a mediocre threshold for The U, consider it's been 14 years in the ACC without so much as a division title.

"We're just trying to be great," said Richt, a former Canes quarterback who graduated a year before Miami actually was great for the first time in 1983.

Get in the van. We're going on that road trip to explore this new region. We're not even stopping by Florida and Florida State, where Jim McElwain and Jimbo Fisher each have a pair of championship rings.

Howard Schnellenberger once called South Florida "The State of Miami" because of all the high school talent. Now, its new inhabitants are calling it home.

"Within so many hundreds of square miles," Romberg said, "we have a ridiculous pedigree of coaching."

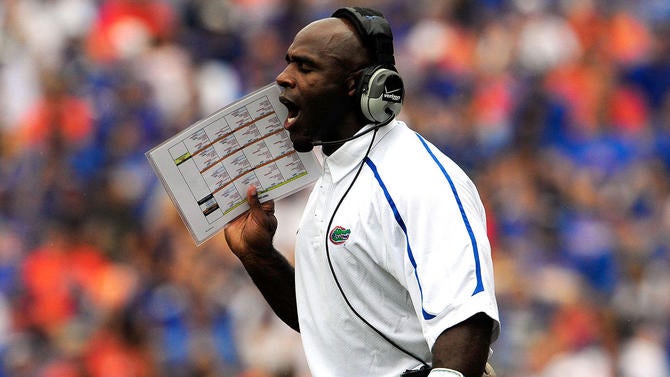

Butch Davis got the call at about 4 a.m. a few months back.

"They were leaving some club in South Beach," said Davis, who immediately recognized the voices of some of his old Miami offensive linemen -- Romberg, Joaquin Gonzalez, Martin Bibla and Bryant McKinnie.

"You could hear them all screaming and yelling. The windows were down," Davis recalled. "They were all packed into the same car."

"That was just us being assholes," Romberg recalled.

"I said, 'Why didn't you take me with you?'" Davis shared.

Sometimes you can't take the Miami out of the Hurricane.

Davis knows there could have been more revelry on his watch. He has no problem admitting his regret for leaving Miami a week or so before 2001 National Signing Day for the Cleveland Browns. By that time, he had done his job as the clean-up coach following crippling NCAA penalties. But his career would never be the same.

"Sure [I regret leaving]," Davis said. "In retrospect, looking back on it, you knew how super talented the team was at the time."

It's widely accepted the national championship Miami won in 2001 was almost all Davis' doing. He coached and/or recruited at least 59 NFL draft picks, 26 of them first-round selections in six seasons as Miami's coach (1995-2000).

The NFL provided financial security and an accomplishment that grows more significant by the year. Davis is the last coach to lead the expansion Browns to the playoffs (2002).

In 2001, then-Browns president Carmen Policy dangled $15 million in front of Davis, whose reputation was sterling having won championships as an assistant with the Hurricanes and Dallas Cowboys.

Then-Miami athletic director Paul Dee made leaving easier. Davis says the school was hung up on contract language: Miami would pay only 20 percent of his deal if he was fired. However, he had to pay 80 percent of his deal as a buyout if he left.

Why not make it 50-50, Davis suggested?

"An NFL team in a heartbeat would pay [a buyout] to get Urban Meyer to leave or Bob Stoops or whoever," Davis insisted. "That would never stop anybody."

At the time, Davis was a hot commodity. So why is he sitting in a modest conference room attached to FIU's Riccardo Silva Stadium that was home to third-worst attendance in FBS last season?

The easy answer? The job was open. Anything beyond that, the explanation gets complicated.

For years, Davis couldn't understand why he was unable to get a sniff after being fired at North Carolina in 2011 amid an NCAA investigation. Over the years, Davis has gladly produced documentation from the NCAA that said he wasn't involved in the wrongdoing perpetrated by his former defensive line coach John Blake.

But the current academic fraud investigation had already bubbled up. While North Carolina landed on probation for the Blake transgressions, Davis landed in the unemployment line.

"The North Carolina stuff -- to be honest with you -- has been an albatross around [my] neck for a while, especially early," Davis said. "… Not one single violation was against me."

Seven years between head coaching jobs and what was left was a friend. FIU AD Pete Garcia and Davis had been together at Miami and the Browns for a total of 10 years.

"He was the first person I called" following the firing of Ron Turner, Garcia said. "Knowing him for 25 years, I know exactly what we're getting."

He's getting an accomplished coach who a few years ago probably wouldn't have touched this job with a feather duster. But when there isn't much else available, you take over a program that has had two winning seasons since it went FBS in 2002.

"Make the big time where you're at," Davis said. "I want to get into the top 20 and top 15."

That would be a reach. The coach uses examples such as Bill Snyder and what he accomplished at Kansas State, or Northern Illinois, UConn and Boise State all playing in BCS and New Year's Six bowls.

It might be easier walking the 12 miles from the FIU campus to the site of Miami's old Orange Bowl home in Little Havana than imaging the Panthers in a major bowl.

"I think this is going to be the last [stop] for Butch," Romberg concluded.

By that he means this being a retirement job for a respected coach whose hair is graying but whose reputation has remained intact.

"We must have had a shot of testosterone," Romberg said, recalling that drunken pre-dawn call. "Calling Butch Davis, even though we're removed and we're all grown men now, it's still intimidating. … But what a great guy."

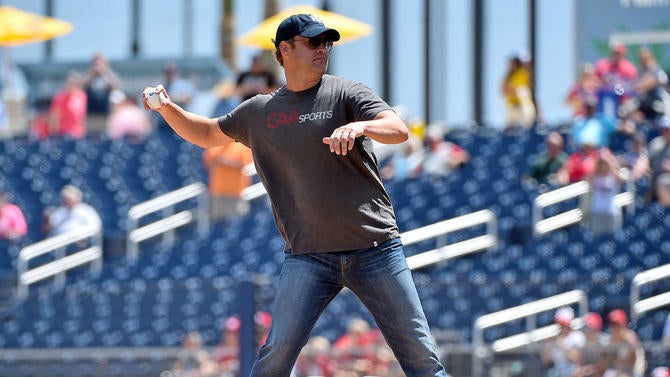

When he came to Boca Raton, Lane Kiffin counted on sun, sand and no more Saban. What he didn't expect was Jeff Kelly, the 62-year-old president of the 47-year old university. And to hear Kiffin tell it, a bit of a fan, too.

"This guy led the interview," Kiffin said. "It was him, the AD and the three biggest money people. He talked more than any of them. He was recruiting me. He knew, if he gets his program fixed, what it does for the university."

While FAU is trying to learn what it's like to be in the big time, Kiffin is trying to relearn being a head coach. Which way this relationship goes, no one knows.

Kelly came to FAU in 2014 from Clemson where he was a vice president for economic development. It's clear he at least is familiar with the big time having witnessed the rise of Dabo Swinney and the Tigers.

"Presidents don't usually come to interviews with football coaches," Kiffin said. "Normally, you get the job and then you got meet the president. … They usually trust the AD to hire the football coach."

His career college winning percentage (.651) isn't what's in question; rather, it's the way Kiffin has gone about the job at times.

Fired just off the tarmac at USC. Disparaged on his way out the door at Oakland by Al Davis. Suddenly one and done -- in the middle of the night -- at Tennessee.

"I can see myself here for a long time," said Kiffin who, took the job in December in the midst of Alabama's run in the 2017 College Football Playoff. "I don't think I could have said that 10 years ago. I was always chasing. 'How fast can I become a head coach?'"

FAU represents some sort of crossroads for Kiffin. His peers on this road trip -- Davis, Richt and Strong -- have some fine career accomplishments as head coaches as well.

But Kiffin has to know that, if he flops in Boca, all that might be left is a career as a play-caller.

That's where Kelly and Florida Atlantic come in. Both sides go into this relationship with their eyes wide open. Kelly is willing to double down on football for his university with an eye-catching hire.

Yes, it's strange that a coach with a hand in four Heisman Trophy winners and three national championships is trying remake himself at a Conference USA school just off I-95.

"It's the perfect place for him to do something extraordinary," said Schnellenberger, the program's first coach.

Kelly is counting on it.

"He wants to be the fastest growing university in the country," Kiffin said. "And he really likes football. He comes to practice. As you get older and get more experienced, you realize how important the president and your donors are."

Kiffin confesses that in the early days he didn't know an endowment from an end run. Faculty athletic representative? Provost?

"I didn't even know what those words were," he said.

Saban and Pete Carroll took care of the schmoozing, the speaking, the fund-raising. Now it's all on him.

And, so far, Kelly isn't about to step in the way. Kiffin offering a scholarship to a seventh-grader was the most Lane thing ever.

FAU has become a sort of Ellis Island for wrongdoers from elsewhere. Kiffin retained former FSU quarterback D'Andre Johnson, who allegedly punched a woman. There are others.

Kiffin's offensive coordinator is Kendal Briles, son of Art, having moved over from scandal-ridden Baylor. The defensive coordinator is brother Chris, who scandal-ridden Ole Miss has blamed for a large part of the NCAA violations.

The group of analysts is growing at a rate at least similar to his last employer.

"We're a mini-Bama," Kiffin said.

That's as close as Boca Raton gets to Tuscaloosa, Alabama. The Owls have played FBS football for 13 years. Alabama has 12 national championships in the wire service era alone (since 1936).

Kiffin still sees similarities. Saban got his first major head-coaching job at Michigan State job in 1995 at age 43.

"I'm that age!" Kiffin gushed.

But is he grown up yet? Even a football-loving president can't answer that one.

The coaching carousel turns so fast we're way beyond considering Charlie Strong taking a mere 19 days to rebound at South Florida.

Now it's to the point that we can see a clear path to his next job. The Bulls have the talent, the schedule and the coach to go 13-0 and head to a New Year's Six bowl. From there, no doubt another Power Five job would be available somewhere.

For now, neither side is disappointed at the current arrangement.

Strong, 56, is much more than an adequate replacement for Willie Taggart, who left USF for Oregon. That's why the possibility of a brief fling in Tampa remains.

"It's not like you're walking into a situation where a guy got fired," Strong said.

The Bulls are coming off a 11-win season and are indeed favored to grab that Group of Five berth. Quarterback Quinton Flowers could chase a Heisman in the process.

Texas is in the head coach's rear view.

"If you sat out and you try to get back in next year, do you get in?" Strong asked himself. "There was an opportunity here. I had to take it."

It took him all of those 19 days to decide after the Texas firing. A burgeoning career had merely been sidetracked, barely delayed. Strong still has those championships at Florida under Meyer. He left Louisville a lot better than he found it.

It was those combined 15 years spent as a Gators' assistant that allows Strong to rattle off the names of high school hotbeds and their coaches around the talent-rich state.

He is home -- at least for a little while. It's hard to talk about a Charlie Strong legacy at Texas. It's been nine months since he lost to Kansas to seal his fate in Austin.

There are a lot of reasons why it didn't work -- bad special teams, inconsistency, bad bounces, worse results.

"I have no regrets," Strong said. "Some guys get upset. I didn't get upset. You feel like you let a lot of people down. That was the hardest for me to overcome."

"He's a very prideful man," said South Florida AD Mark Harlan. "I think he cares about everybody. I think if he felt like he let someone down, he probably meant it."

At Texas, Strong left behind consecutive top-10 recruiting classes at Texas. New Longhorns coach Tom Herman called his first recruiting class "transitional" in February. It was also the lowest-ranked (26th) in school history.

Any success Herman achieves in the future will have been in some small way because of Strong. As the new USF coach summarized: The cake has been baked at Texas. All it needs is icing.

The question now is how long will Strong going to be sweet on South Florida?

For once, a Miami coach looks completely relaxed.

The daily pressure of trying to live up to a national championship legacy is there, but Richt is used to it. This is a guy who coached 15 years at Georgia, won two SEC titles and got his team to three BCS bowls.

This is a guy who helped win two national championships and routinely coached in several epic Florida State-Miami games as a valued Bobby Bowden assistant.

Yes, Richt has the look of a man who has it all under control. The Canes won their last five in a row in 2016, ending the season with a bowl win for the first time since 2006.

"The state of Florida hit the jackpot with some really good coaches," Richt said, hopping on the angle of this story.

Obviously, he lumps himself in that group. Even when Larry Coker inherited the last national championship in 2001, there was the feeling he was a caretaker.

There is a future with Richt, one of the few people to play for, beat and be hired by Miami.

"We want to be the first Miami team to win the Coastal Division, to win the ACC," defensive end Demetrius Jackson said. "The time to win is now."

Neither of those things has happened since Miami joined the ACC in 2004. Since then, Coker, Randy Shannon and Al Golden failed chasing that legacy.

In the middle of Richt's first season, though, a national championship player from the 1980s told Jackson, "You have more talent than us. [The difference is] we worked hard and wanted it more."

Miami won't be favored to win that first division or ACC title. In fact, it's a different ACC than Richt entered with Florida State in 1992. There is depth of both teams and coaches. It would be harder today for FSU to finish in the top four 14 years in a row as it did from 1987-2000. ACC players have won two of the last four Heismans. ACC teams have won two of the last four national championships.

Richt is trying to achieve this turnaround playing in what is -- for now -- the toughest conference in the country. He's on his way. If not for Brad Kaaya leaving early for the draft, the Canes might have started out in the top 10. Miami does return one of the toughest front sevens in the country.

All that recent malaise and Miami still has the No. 3 recruiting class for 2018, behind only Texas and Ohio State in 247Sports Composite rankings.

In a town with pro sensibilities, the coach knows it can get real ugly, real quick. They basically ran Golden out of town, flying derogatory banners over the stadium on game days.

"I'm sure there will be plenty of time for that," Richt said, still looking relaxed in this new football state of Florida.

This redemption road trip ends in less than a month. Then they'll want real results -- for Lane in his remake, Butch in his reboot, Charlie in his redo, and Richt in Year 2.