Why defenses are trying to Stack up with spread offenses dominating throughout college football

There's one defensive concept in particular that's growing in popularity

The seeds of college football's most popular defense reside in the recesses of a 75-year-old coaching mind. Joe Lee Dunn's time has largely come and gone, but the game owes the coaching veteran something more than a passing mention heading into the 2021 season.

It owes him a place in history.

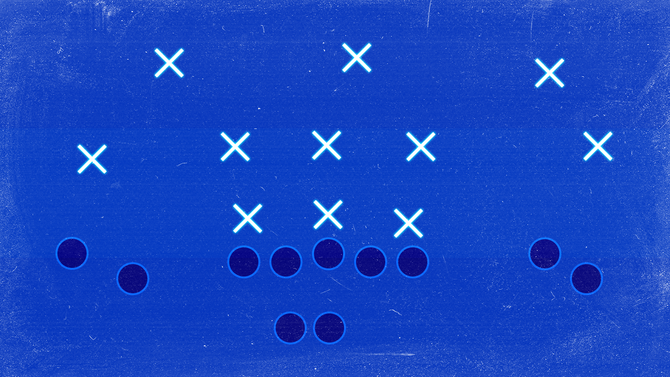

Dunn is credited with helping refine the 3-3-5 "Stack" defense. He brought it with him from Tennessee-Chattanooga to New Mexico as an assistant in 1980. As is the case today, there was a dearth of defensive linemen on that team. Lacking superior strength up front, Dunn's idea was to put as many players as possible behind the defensive line to run and tackle.

Size didn't necessarily matter. Smarts and guts did. He called them "fire ants".

"[It's] a chance to put more athletes out on the field," explained New Mexico coach Danny Gonzales, one of Dunn's disciples. "It's the go-to defense against the spread."

That defense -- or variations of it -- has indeed become the dominant weapon against spread/Air Raid offenses that are dominating the game.

Alabama puts five defensive backs on the field at least 80% of the time, according to defensive coordinator Pete Golding. The more common 4-2-5 alignment is a direct descendent of the Stack. Iowa State has turned around its program by adopting the concepts. TCU coach Gary Patterson has made a career out of utilizing the 3-3-5 -- putting hybrid players on the field who can play cornerback, safety and linebacker, sometimes changing positions from one play to the next.

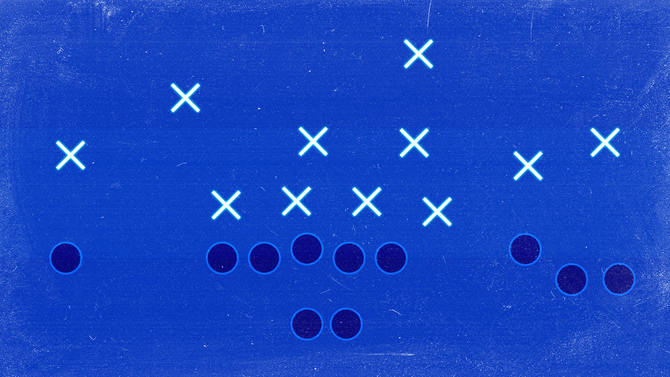

4-2-5

3-3-5

Defensive linemen remain in short supply. After being overrun the last 15 or so years by modern offenses, defenses are clawing back strategically.

"The [need for] true four-down lineman, three regular linebackers and four secondary guys is gone," said veteran coach Rich Rodriguez, now of the offensive coordinator at Louisiana-Monroe. "Everybody is playing with the nickel stance, five defensive backs. Whether it becomes a 4-2 front or a 3-3 stack look is where it's heading on all levels."

The average number of plays where defenses have fielded at least five players in the secondary has increased each year since 2016, according to Pro Football Focus. In 2020, that figure (36.3) accounted for approximately half of the average plays per game.

Jon Heacock had spent 30 years coaching at 10 different stops when Matt Campbell hired him as his defensive coordinator at Toledo in 2014. When Heacock followed Campbell to Iowa State in 2016, he originally ran a 4-3 defense. But three games into the 2017 season, everything changed. Heacock scrapped the 4-3 for the 3-3-5. Iowa State held eight of its final 10 opponents to 20 points or less, an uncommon run in the Big 12.

Since that defensive switch, the Cyclones are 31-17 having gone to four straight bowls for the first time while becoming a player on the national stage. They start the season ranked No. 7 in the AP Top 25, the highest preseason ranking in program history.

Further Iowa State magic: The Cyclones ranked last in the country last year playing man coverage only 7% of the time. That actually translated to excellence. In 2020, Iowa State posted its best defensive season in 16 years, allowing 340 yards per game (second in the Big 12). The Big 12's best defensive team, West Virginia, played man only 8% of the time.

Clearly, the ability to develop those hybrid players is key. Since 2017, when Heacock made his midseason decision, the Cyclones drop eight men into coverage a nation-high 21.3 snaps per game. Even more impressive, they are in the middle of the pack among Power Five teams in that category, allowing only 6.58 yards per play.

Sure, some of that is the result of playing in the pass-happy Big 12. It's also Heacock and Campbell figuring out what it takes to win.

"It started with [Heacock] at Iowa State, and there are spinoffs on it," North Texas defensive coordinator Phil Bennett said. "It's probably been the best matchup."

All of it has led to new defensive language. A "hyper-light" box is a three-man front that breaks down modern spread defenses to an essence: stopping the run with as few people as possible. The fewer the better to defend the pass downfield.

In the 4-2-5 Stack era, the most desirable might be "half players." those able to both rush the passer and drop into coverage. Anything to throw enough momentary confusion into the offense to slow the speed of the spread. That's the main advantage.

The disadvantages?

Verticals: The best way to beat the Stack is for all the pass catchers to run straight streaks toward the end zone. "It always comes down to the four verts," one former Big Ten defensive coordinator said. "How are we going to cover four verts?"

Pressure … or lack of it: With only three down linemen to confront, offensive lineman can outnumber the defense.

Stopping the run: With that many defenders at the second and third level, savvy offensive coordinators will simply run the ball and physically dominate.

This a world where Mike Hankwitz walked into the retirement sunset with a mic drop. There used to be a time when veterans like Hankwitz didn't have eight players on the entire roster who could cover pass catchers. Against Ohio State in the Big Ten Championship Game, Northwestern's defensive coordinator decided to drop seven and eight into coverage against Justin Fields. Ohio State's great quarterback was sacked three times and threw for a career-low 114 passing yards.

In Hankwitz's final season at age 72, he showed an amazing ability to adapt. Northwestern led the Big Ten and ranked fifth nationally in scoring defense. Safety Brandon Joseph was a unanimous All-America selection as a freshman, tying for the national lead with six interceptions. The Wildcats finished in the top three in average snaps per game playing at least five defensive backs. They led the country playing with seven-man coverage almost 34 plays per game.

"The spread offense has changed things dramatically because people started getting more skill on the field," Hankwitz said. "Short, quick passes. The run game trying to stretch you out. The biggest thing was the running quarterback. You add that, you add another gap to the defense."

Something changed in the SEC after Mississippi State set the conference passing record in the 2020 opener at LSU. The Tigers suffered an embarrassing loss, defensive coordinator Bo Pelini lost face, and the SEC adjusted. Instead of trying to take on Mike Leach's receivers man-to-man, defenses played more blanket coverage.

The Bulldogs never adjusted back. While Mississippi State ran the most offensive plays against five-, six-, seven- and eight-man coverages last season, its production suffered. The Bulldogs' yards per play facing those coverages ranged from 91st to 109th nationally.

Gonzales begins his second year as the Lobos coach. Being a disciple of Dunne's is the reason he hired Rocky Long as his defensive coordinator. Forty-one years ago, Dunn joined Long on Joe Morrison's New Mexico staff. In their one season together, Dunn passed along 3-3-5 concepts.

Dunn eventually became head coach at New Mexico and Ole Miss, among his nine subsequent stops over the next 32 years. As Mississippi State's defensive coordinator from 1996-2002, his defenses went from 47th to 35th to 20th to leading the nation in 1999. That year, he was a finalist for the Broyles Award (best assistant coach) for a Bulldogs team that went 10-2 and beat Clemson in the Peach Bowl.

Long went on to coach New Mexico for 11 years and San Diego State for nine. Urban Meyer lost two games in his two seasons at Utah. One was to Long and the Lobos in 2003. Under Long, San Diego State won at least 10 games in four seasons. That equaled the program's previous total in its history.

Gonzales played safety, backup punter and coached under Long at New Mexico. He then became Long's defensive coordinator with the Aztecs before joining Herm Edwards in the same capacity at Arizona State from 2018-19.

When Gonzales needed a defensive coordinator at New Mexico, one of the first things he did was call the 71-year-old Long.

"When I was the head coach at New Mexico, Joe Lee would come through here every year," Long recalled. "Sometimes, he'd sit for a day, maybe a day and a half, and watch our film. At the end of that, he might have one or two questions, and he'd be out of here."

Onto his offseason vacation in Las Vegas.

The three coaches have been linked throughout their careers. The defensive philosophy they share has come back in style.

"Obviously, they're scoring more points [these days]," Long said. "It's much more difficult to stop, partially because of rules. You can't touch quarterbacks. … The rules are such that the defense could be aggressive enough to slow people down, but you can't intimidate anymore. You have to be more finesse because very few people are lining up trying to pound the ball. Nobody's patient."

Not anymore. The last defense giving up single-digit points per game was Alabama in 2011 (8.2 points). Auburn won a national championship the previous year allowing 24 per game. Last year's four College Football Playoff teams (Alabama, Clemson, Notre Dame, Ohio State, Clemson) on average allowed slightly less than three touchdowns per game.

"Defenses always come around," Auburn coach Bryan Harsin said. "Offense kind of got the upper hand. Defenses will come back around. One of the things as you saw the spread get more popular, defenses got faster. Then it was, 'All right, they're kind of balancing it out again,' so teams started running the ball more."

In 2020, that run ratio (54.8% pass, 45.2% run) was the most lopsided it had been since 2014. Scoring is down slightly since there was a record 30.04 points per team in 2016.

Elsewhere, it's the peripheral stats. Texas A&M (third in time of possession in 2020) keeps its defense off the field by holding the ball. Jimbo Fisher's teams have led the conference in that category four of the last five years. Turnovers matter. Eight of the last 12 national championships have finished among the top 20 in total takeaways. Alabama is the only champion since 2009 to finish in the top 10 twice in that category (2009, 2020).

Eliminating big plays helps. Georgia did it better than anyone last season allowing explosive plays on only 4.5% of snaps. (Explosive plays are runs of 10+ yards and pass completions of 30+ yards.) You shouldn't have to be told how good Georgia has been defensively under Kirby Smart.

In the 4-2-5, the most important defensive player on the field is the high safety, sometimes called a "star". Each program uses different terminology. Regardless, that defender must have the hands of a pass catcher, the powerful legs of a running back and the tackling ability of a hard-hitting linebacker.

Think of Brian Urlacher, the Pro Football and College Football Hall of Famer who once made 178 tackles as a junior at New Mexico. Under Long, Urlacher was a cross between a linebacker and free safety in the 3-3-5 who also returned kicks and caught passes. In eight of his 13 NFL seasons, he was a Pro Bowl selection. Urlacher may not have been the first, but he's certainly among the best of what are now known as those hybrids.

"It's really hard to take a linebacker in college and teach him to back peddle and cover," said Gonzales, also Urlacher's former teammate. "If you're going to put a safety in there, he has to be as courageous as they come. … He has to take on linemen, run over them, run through them, whatever. You have to find a special kid who's not afraid to play down in the box but also cover in space."

Somewhere, Joe Lee Dunn is smiling. In some small way, he made Urlacher possible. In a big way, he is the mastermind behind the scheme that college football teams use the nation over.