Will Michigan finally prove itself a legitimate contender in third College Football Playoff semifinal?

The Wolverines have not been a beacon of success in CFP play but can make a major statement otherwise on New Year's Day

LOS ANGELES -- This just might be the best Michigan team -- ever. It also has a chance to be one of the College Football Playoff's biggest underachievers. As a third straight CFP semifinal awaits the No. 1 Wolverines, both possibilities hang in the air like a shanked punt in the warm California sun.

Just don't try to pick a side yet. Like its coach, Michigan as a program is a contradiction wrapped in a riddle covered in mystery.

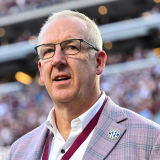

The betting favorite to win the 10th CFP, beginning Monday in the Rose Bowl semifinal against No. 4 Alabama might have the toughest road of the four participants. Because of various, sundry suspensions of Michigan's head coach, offensive coordinator Sherrone Moore actually has four wins as acting game-day coach.

Meanwhile, Jim Harbaugh reportedly has an extension offer on the table that would make him one of the highest-paid coaches in the game's history. Why would he sign it -- especially now -- with more NFL jobs coming open by the day? At least one of those openings (Los Angeles Chargers) is at a place he is fondly remembered as the franchise quarterback.

"That's a question you get every year, 'He's going to leave,'" wide receiver Roman Wilson said. "I don't know. I think only he knows."

On a certain level, it doesn't matter. Nothing seems to faze these Wolverines, not even playing without their coach.

Two NCAA investigations -- possibly involving major penalties -- hang over the program. A lot of the "distractions" players were asked about at media availability this week have been self-inflicted. A buttoned-up strategist who oversees a program with the fewest penalties in the nation this season (38) has been accused of pushing the boundaries on ethics to get to the top in the sign-stealing scandal.

"Coach likes to talk about it like it's a hidden blessing," Wilson added. "Without adversity, you're not going to become something special."

Let's not make Michigan a victim. On the field, it has won every game. Those players have earned every bit of what they have achieved. But off the field, the program has been dysfunctional at times. The names Weiss, Partridge and Stalions sounds like an Ann Arbor, Michigan, law firm. Instead, they are two assistants who have been fired in the last year (Matt Weiss, Chris Partridge) and the infamous Connor Stalions.

How hard can excellence be with all these odd, fascinating, disturbing head winds? Nothing seems to faze these Wolverines.

A team that has won 31 of its last 33 games is one loss away from becoming only the second team in CFP history to be knocked out of three consecutive semifinals. It's a fine line between a magical journey and being a team that can't win the big one. Just ask Ryan Day.

Just ask Harbaugh, in a different way. Is Michigan truly a national power or merely a national pretender? Consecutive 13-win seasons for the first time in program history suggest the former is accurate. The only result that matters will decide the latter.

Over the last three seasons, Michigan has been good enough to blow through the Big Ten. In the CFP, it has been exposed -- two years ago by a runaway Georgia on its way to a national championship, last year by an 8-point underdog TCU that was either underrated or undervalued by Michigan. Maybe both.

"Last year, when it was needed, we didn't have it," said Michigan EDGE Jaylen Harrell. "Communication wasn't there, our angles and tackling wasn't there."

The Wolverines gave up 51 points in that national semifinal to a Horned Frogs team that lost by 58 in the CFP National Championship as the Bulldogs won their second straight title. The last time Michigan gave up that many points to a team not named Ohio State was 2000.

So, the question lingers: Are the Wolverines built for the playoff? Because something changes for them this time of year.

There are the usual whispers that Michigan is tough but not tough enough, fast but not fast enough.

"Just [that] Michigan can't beat an SEC team," said Michigan defensive back Rod Moore of those whispers, "and that they are too fast, we can't run with them, which I mean, we'll see on Monday."

We absolutely know what we're going to get with Michigan in the Rose Bowl, and that might be part of the problem. Harbaugh is going to pound the rock with Blake Corum and Donovan Edwards (combined 5,000 yards, 67 touchdowns rushing in their careers) and dare the other team to score.

Again, that strategy has worked this season to the point we can make the best-ever assertion about Michigan.

If coordinator Jesse Minter's defense keeps the current scoring average under 10 points (9.5 this season leads the country), Michigan would be the first team to average less than double digits defensively since Alabama in 2011.

Will it be good enough to make an ultimate impression on the national stage?

Perhaps the other three CFP participants have more upside. Alabama has turned a once-disastrous season into Nick Saban's best coaching job. Texas can absolutely prove it is "back" by winning out. A compelling case can be made for Washington -- the only other undefeated Power Five team in the field -- being that No. 1 seed instead of Michigan.

Harbaugh's bunch? We've sort of seen Michigan's ceiling. This is their playoff close up in La La Land.

Will the unanimous No. 1 team in the nation blink?

Any argument against starts with an age-old trope. The Big Ten is top heavy. It's only realignment that has changed. Back when there were 10 teams, it was the Big Two and Little Eight. Now, it's the same Big Two (Michigan, Ohio State) and a Little 12 in the 14-team league.

Lately, even Ohio State isn't in the discussion because Michigan has been so dominant.

"You don't have your head coach for about six games of the season and you still go undefeated," Moore added. "It makes you a strong team overall."

But again, Michigan's path to the Promised Land is the toughest of the field. Alabama, an underdog in consecutive games for the first time since 2007, will be difficult to take down coming off its upset of Georgia in the SEC Championship Game. Then Michigan would get either the game's leading passer in Michael Penix Jr. or the best Texas team since 2009. As you may have heard, the Longhorns have already beaten the Crimson Tide.

Two strange trends have emerged out of the CFP. (1) The semifinals have mostly been blowouts. (2) The No. 1 seed rarely wins.

In fact, being No. 1 in the playoff has been a curse of sorts. Only three of the prior nine No. 1 seeds have won it all. It wasn't until Year 6 that LSU broke through in that epic season that still might be the best by any college team. Alabama followed in 2020. Georgia did it last season.

Michigan is a proper No. 1 seed this year, but what does that really mean in arguably the most loaded CFP field since the tournament's formation?

"Coach, he says he doesn't hold grudges, but he remembers," Michigan linebacker Junior Colson said of Harbaugh. "That's the way he lives. … That's the way we all live by. We remember everything that's happened, everything media have said, anything anybody ever said, anything anybody's ever done."

Three years ago, Michigan was 2-4 during the COVID-19 season, and Harbaugh's job security was in question.

"We were not a good football team," explained offensive lineman Trevor Keegan. "We weren't tough. We were sloppy. Nobody cared. Nobody wanted to be in [the football facility]. It was some dark days because you're playing for Michigan, and you're supposed to be on the biggest stage."

Keegan described how Harbaugh sent an email detailing to players how they were going to turn the program around together. It worked to a certain extent.

Michigan contended that it learned its lesson after losing to Georgia by 23 points in the Wolverines' first CFP appearance. Then they went out and lost to TCU last year.

So, does Michigan really mean it this time? Because Harbaugh's ineffectiveness in the CFP threatens to overshadow his (alleged) sign-stealing effectiveness.

Oklahoma (2017-19) is that only other team to lose three consecutive CFP semifinals. You might have noticed neither the Sooners nor Lincoln Riley have been back since.

That's a legacy no one wants. That's a pattern Michigan wants to change.